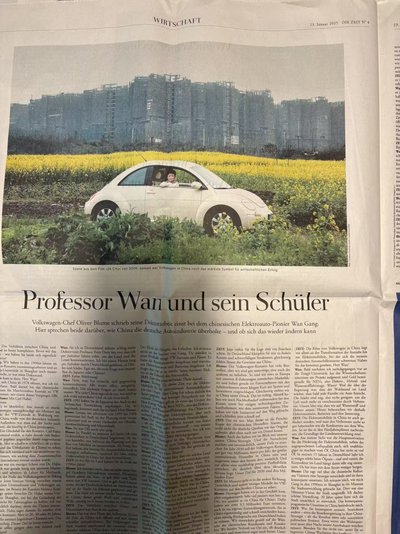

Professor Wan and his student

Volkswagen CEO Oliver Blume once wrote his doctoral thesis with Chinese electric car pioneer Wan Gang. Here they both talk about how China overtook the German car industry - and whether that can change again.

DIE ZEIT: The relationship between China and Germany today is complicated. Before we discuss this - how did you two actually get to know each other?

Wan Gang: We worked together at the Volkswagen Group in the 1990s and also did research together at Tongji University in Shanghai; he was my doctoral student.

ZEIT: How did that come about, Mr. Wan?

Wan: When China opened up in 1978, I was a young man. Soon afterwards, the Chinese Ministry of Mechanical Engineering got in touch with VW, with one of your predecessors, Olli.

Oliver Blume: With Carl Hahn!

Wan: Exactly.

ZEIT: It is said that a minister from China arrived unannounced at the VW headquarters in Wolfsburg on a Monday morning: China wanted to learn from German industry. They were also looking for manufacturers who would produce in China in the future.

Blume: A stroke of luck for the Group. Carl Hahn once told me that there were many doubters at the time about this unfamiliar business. But he eventually managed to convince them and see the unknown as an opportunity. At the time, no one could even begin to imagine how important this collaboration would become for the company.

Wan: That was a courageous move on Dr. Hahn's part. In 1984, when I had just finished my master's degree and was working as a teacher of mechanics, the first joint venture agreement between a Chinese company and Volkswagen was signed in the hall of the People's Congress in Beijing, in the presence of Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

Three days later, Dr. Hahn visited my university in Shanghai to help establish the Department of Automotive Engineering. I was very happy because I was interested in the subject. Hahn said at the time: "Many Germans will come. But in 20, 30 or 40 years, most of the engineers would be Chinese. That was far-sighted. This goal has been achieved today.

ZEIT: But you yourself went to Germany first?

Wan: Germany was known as a highly developed country, my tutor in the Master's program had studied in Germany. So I seized the opportunity of those years, went to Clausthal-Zellerfeld in 1985 and did my doctorate there.

ZEIT: How did you experience the Federal Republic of Germany?

Wan: When I arrived in Germany, my doctoral supervisor, Professor Peter Dietz, suggested that I hitchhike to get to know the country and the people. I spent a month hitchhiking through Germany, visiting villages and towns. No matter where, the first question was always: Are you Japanese or Chinese?

ZEIT: No rejection?

Wan: No, we tried to get to know each other. Everyone was open, curious and friendly. The next questions I was always asked were: What does China actually look like, how will it develop? And whether I wanted to go back.

ZEIT: In 1991, you started as an engineer in Technical Development at Audi. That's where you came in, Mr. Blume, in Ingolstadt.

Blume: Exactly, we worked together at Audi from 1995 to 1998 on the planning of a new paint shop and on new methods for surface coating and measurement technology.

Wan: Olli was still very young then.

Blume: Yes, at the same time as my job, I had started a doctoral thesis in Germany on using software to support the planning and construction of factories. When Gang got the call to set up the Institute of Automotive Engineering in Shanghai, I had the idea of continuing my doctoral thesis in China with him.

ZEIT: What kind of country did you end up in at the end of the 1990s?

Blume: I remember hundreds of cyclists waiting at every red light. Private individuals rarely had a car, but there were lots of cabs, mostly VW Santanas. And there were Audi limousines. At the university, students worked and studied late into the night in the lecture hall. I always find that remarkable in China: this great diligence and unconditional will to constantly improve.

ZEIT: The relationship between China and Germany was different back then.

Blume : That was a phase of new beginnings. It was a time when China was opening up and industrializing faster and faster. Volkswagen and Audi increasingly recognized the enormous market opportunities. China progressed much faster than India, for example, after these two huge countries had developed almost in parallel for several decades.

ZEIT: Why was Germany, and Volkswagen in particular, involved in this growth so early on?

Blume: Because the cultures fit together well. The diligence, the ambition, the inventiveness. I remember the Gang Institute. There were some VW Santana and Passat cars in a test hall. He had removed the gasoline engines and installed electric motors and batteries instead. I asked him what he was doing. His answer: Electric is the future of the automobile.

ZEIT: A rather surprising thesis at the time ...

Blume: That's right. At that time, electric mobility was a utopia for the international automotive industry. But Gang firmly believed in it even then. From today's perspective, that was visionary. That is why he is considered one of the forefathers of new energy vehicles, or NEVs for short, i.e. electric, hybrid and hydrogen vehicles. He is certainly the most important electric pioneer for China, but he is also an important figure worldwide.

Wan: The environmentally friendly drive of cars - whether with electricity or hydrogen - has always been my dream. I went back to China from Germany to realize it.

ZEIT: Volkswagen's growth is now over and the company has become the pursuer of Chinese suppliers. Would you have thought that as a young engineer, Mr. Blume?

Blume: It was always clear to me that such a country would one day develop its own car industry. But we should look at the whole story: With the Volkswagen Group, we have given millions of people access to cars and supported the development of a strong local car industry. In doing so, we have contributed to growth and prosperity. Not only in China, but above all in Germany. We are proud of that. And now the market has indeed changed. A competitive automotive industry has developed in China in a short space of time. For us, this is now a kind of fitness center.

China as a good example

ZEIT: What do you mean by that?

Blume: Innovations, for example in batteries, software or autonomous driving, are developed here pragmatically and cost-efficiently, with a high level of creativity and immense speed. Productivity is high and there is close cooperation between politics, science and industry. We now see this as an opportunity, have adapted to it and are also working intensively with local high-tech companies. We can use this know-how and this attitude to transfer it to the entire Volkswagen Group, especially to Germany, where we have enjoyed our former success for too long.

ZEIT: But now you're making light of the situation. In Germany you are struggling with high costs and cumbersome structures, while at the same time you are missing out on profits from China.

Blume: The Volkswagen Group has many construction sites, but we are well on the way to rectifying them one by one. For example, we are now the market leader in Europe with our e-vehicles and have embarked on a smart course of saving and investing in agreement with our employees. At the same time, we are under pressure in China. That is correct. At the moment, we still have some catching up to do, particularly in terms of costs and some technological topics of the future such as autonomous driving. We have launched many initiatives here and are now catching up quickly.

ZEIT: That is necessary. Just think of the Porsche copy from Chinese manufacturer Xiaomi, which probably doesn't have the same quality as the original, but only costs a third as much.

Blume: We also have that in mind with our new China strategy. And the progress we are making makes us confident that we will achieve our goals: In 2030, the Volkswagen Group should be the largest international manufacturer in China with a good four million cars per year and among the top three overall, of course. And, above all, achieve sustainable positive profitability that is significantly above the current level. Our target for 2030 is three billion euros.

ZEIT: At the moment, things are moving in the opposite direction. In fact, fewer and fewer VW Group models can be seen on the roads in China.

Blume: That's why we have completely restructured the business: a lot is now happening here locally, we call it "in China for China". We have invested around 3.5 billion euros in this, including in our own development center, which can make decisions independently and quickly in China without having to constantly consult with Germany. We develop specifically to meet the wishes of Chinese customers.

We buy technology locally, often much cheaper and sometimes even better. Our goal is to design cars in China in three years instead of four and to reduce the manufacturing costs of electric vehicles by up to 40 percent. We are already on the right track, we will deliver - but the next one to two years will still be challenging.

ZEIT: Volkswagen's crisis in China is mainly due to the transformation of drive systems towards electromobility, which most German automotive companies are struggling with. Did you see this coming, Mr. Wan?

Wan: Soon after I returned to Tongji University, the Ministry of Science set up a project and provided funding for NEVs, i.e. electric, hybrid and hydrogen vehicles. Why? Because the government's idea was that the country's prosperity was growing and that every family would soon need a car. The cities are cramped, so it's not suitable to pollute the air even more with combustion engines. Our idea was to focus on hydrogen and electricity. Today, we have mastered electric motors, batteries and their control systems.

ZEIT: Electromobility in China has also been promoted because the combustion engine was not as well mastered as the competition from the West. This can be read in the five-year plans that form the basis of the country's development.

Wan: In my view, the main motivation for promoting electromobility, apart from the air quality I mentioned, was also to become less dependent on oil. China doesn't have that much oil. In my 15 years in Germany, I've seen the price of oil go up and down, and the country's economy is very closely linked to this. You don't have to worry so much about electricity.

Blume: That says a lot about Chinese culture: developing a strategy from visions and then implementing it consistently. I remember Gang taking me to an urban development museum in Shanghai in the 1990s. There was a miniature vision of the city on display. I thought: nice idea. 20 years later, the city had actually developed like that. I am impressed by the consistent, pragmatic implementation in China.

ZEIT: What you call consistent is described by others - such as the German government in its China strategy - as the result of a very authoritarian political system. For example, when old residential areas have to make way for new highways virtually overnight. Aren't you ignoring this when you describe China's growth so enthusiastically?

Blume: Firstly, consistent action has nothing to do with a political system. Secondly, we take responsibility: the guiding principles of the United Nations for the economy are the benchmark for everything we do. This is non-negotiable. And we also combine this with our activities in China. The country accounts for a third of global economic growth, and we want to continue to participate in this. And if we remain strong and successful, we can use this position to exert influence and enforce principles. That applies everywhere, including in dialog with China.

ZEIT: Is it fair to say that Volkswagen is under so much pressure because Professor Wan was so successful so quickly with the drive revolution?

Wan: It didn't catch on that quickly, it's been 24 years that we've been working on it. The program for New Energy Vehicles was launched in 2001. For a good ten years, we concentrated on in-depth basic research, technological innovation and demonstrative applications. That was a tough time for me. Only occasionally was there positive public attention. For example, we provided 50 electric buses, 20 hydrogen fuel cell cars and two hydrogen fuel cell buses for the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

ZEIT: Back then, in 2007, you were also appointed to the government as Minister of Science.

Wan: Yes, and when we in the government decided in 2011 to really roll out electromobility, it took another ten years. First public transport was to go electric, then private transport. In 2015, only one in a hundred cars was electric. In 2020, the proportion was 5.4 percent. Then it went up quickly. Today, we are at around 50 percent. Sounds easy, but it's been a long road.

ZEIT: What can we learn from this for Germany, Mr. Blume?

Blume: In order to change something big, we need consistent, long-term strategies that go beyond individual government constellations. Rapid changes during a transition unsettle people and managers.

ZEIT: Does that mean you are calling for an end to Germany's back and forth on electromobility and for Europe to stick to phasing out combustion engines in 2035?

Blume: We have invested heavily in e-mobility and are working towards new vehicles in Europe being 100 percent electrically powered from 2035. And we can't question our decisions every three or four years. But for the ramp-up to be successful and actually serve climate protection, we need moderate electricity prices, with electricity from renewable energies, a strong public charging infrastructure and incentives to buy. China is setting a good example in all these areas.

ZEIT: Mr. Wan, electromobility in China has also become established because the state has promoted it with enormous subsidies. The European Commission complains that this unfairly distorts competition.

Wan: Our state support only serves to ensure that the technology matures. But the research is far from over.

ZEIT: The EU Commission has presented detailed figures on how China is distorting competition. Can you understand the criticism?

Wan: Let's look ahead and find solutions together. The EU Commission and the Chinese Ministry of Commerce are still negotiating. They are looking for solutions on both sides.

Blume: To be clear: the German and European car industry do not share the opinion that the European market only needs to be protected from Chinese imports with tariffs.

ZEIT: But tariffs can play a role, that is also the attitude of many European companies.

Blume: The overall aim should be to design tariffs intelligently. They could be coupled with investment incentives: manufacturers who come from China and produce in Europe, create jobs and work with local partners should have to pay fewer customs duties. Let's take battery cells as an example: China is the world's number one in this area. If Chinese companies now manufacture batteries in Europe, our continent can benefit technologically and economically. It could be similar for vehicles. In turn, the same should apply to European companies in China.

Wan: Chinese industry is also prepared to conduct joint research with Europe. And to invest together. That is the best way to achieve common goals.

ZEIT: But the opposite is happening right now: it's not just about the threat of a trade war. There are also fewer student exchanges, the German Academic Exchange Service fears restrictions on academic freedom in China and there are fewer flights between Europe and China. Who is losing interest in whom?

Wan: I think the three years of the pandemic were mainly to blame. Before corona, we had more than 1,000 German students at Tongji University. But we want to get there again. In 2016, I was appointed honorary professor at Clausthal University of Technology and offered classes directly to students and colleagues. I hope that there will be opportunities to continue academic exchanges in the future.

"The life of the Chinese takes place in the car"

ZEIT: Isn't this disillusionment also due to the fact that Europe is afraid of China's speed and market power? E-car companies in China, for example, are now producing so much that they can no longer sell their vehicles on the domestic market and are therefore exporting more and more.

Wan: 84 percent of the cars produced in China are sold in China, so the domestic market is huge. Europe shouldn't worry so much, the continent is economically stronger than China.

ZEIT: Still.

Wan: In the process of reform and development, Europe has been China's role model, we will still learn a lot from the European side in the future. At the moment, the situation is somewhat complicated, yes. But we should see this as an opportunity for discussion in order to find a common path that benefits both sides. I'll give you just one figure: there are 350 million cars in China, which equates to 240 cars per 1,000 inhabitants. In Europe, the ratio is 560 per 1,000, so our market is still large.

The desire of all those people who have escaped poverty is to have their own vehicle. And we will offer them electrified vehicles. Also think about the Global South, as it is now called. It is a market opportunity for everyone. And it is still an obligation for the car industries to bring these societies cars that run without oil and without pollution.

ZEIT: But can this be done in partnership? The EU has clearly stated the differences: In Europe it is the individual that counts, in China it is the collective. The German government describes China as a partner, competitor and rival.

Blume: I think competition is important because you have to make an effort and it leads to further development. It's like in sport: if we avoid all competition out of fear, then we won't get any better.

Wan: We still have the feeling that we are primarily partners. We should use the foundations we have built up over the last 40 years.

Blume: Take Volkswagen. We have around 90,000 employees in China, over 9,000 partners in the supply chain and over 3,000 in retail. Behind this are many personal relationships across continents. We are a commercial enterprise and build cultural bridges at the same time.

Wan: I also don't believe that they are all alienating each other. There are many Tongji alumni among Volkswagen employees in China. They work creatively and diligently and have integrated well into the VW family.

ZEIT: But China and Europe are also moving away from each other in automotive technology.

Blume: The days when the German car industry developed a vehicle in Germany and only adapted it a little in China are indeed over. There are increasing differences, especially in terms of customer expectations: Chinese people's lives take place to a large extent in their cars. They want more technology than Europeans. For example, all functions in the vehicle must be operated by voice. Analog buttons are largely superfluous.

And large screens are needed to watch movies or sing karaoke in traffic jams. There are also differences in regulation, for example in terms of software and data protection. In this respect, it is foreseeable that two independent technological ecosystems will emerge in Europe and North America compared to China. But the Volkswagen Group can handle this very well because we are rooted locally everywhere.

Wan: When we started together in 1984, China and Volkswagen, it was much tougher. There was a Cold War, the world was really divided. And yet we worked together. Since then, a connection has grown that is stronger than the current pressure that threatens it. I think China and Europe have major strategic goals in common.

ZEIT: In which areas?

Wan: In green energy, health, food supply, climate change. This forces us to cooperate. We had a hot summer this year in many provinces and cities in China, no one can hide from that. Nature connects us with each other. It forces us to negotiate to find a mutually acceptable solution and work together for sustainable and common development.

Original: https: //www.zeit.de/2025/04/autoindustrie-vw-oliver-blume-wan-gang-china